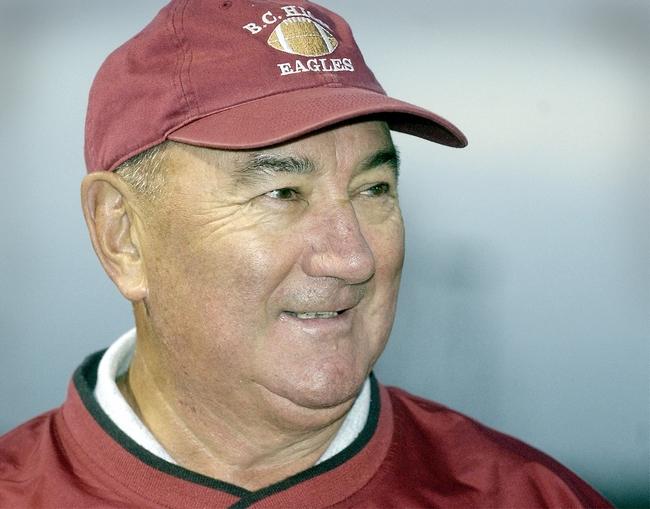

James Cotter

Click the button below to make a donation in memory of James Cotter

Published in The Patriot Ledger on July 20, 2010

Legendary Boston College High football coach James Cotter died early Tuesday morning after a four-year struggle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was 73. Cotter, who grew up in Dorchester’s Savin Hill neighborhood, lived in the Wollaston neighborhood of Quincy. He coached at BC High for 41 years before retiring in 2004.

QUINCY

Legendary Boston College High football coach James Cotter died early Tuesday morning after a four-year struggle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was 73.

Cotter, who grew up in Dorchester’s Savin Hill neighborhood, lived in the Wollaston neighborhood of Quincy. He was diagnosed with the illness in 2006.

He coached at BC High for 41 years before retiring in 2004. His teams had a lifetime record of 236-149-17, and he guided the Eagles to Eastern Mass. Super Bowl championships in 1977 and 2000.

Cotter was also the school’s athletic director for many years.

Cotter won a scholarship to attend BC High and was a two-sport athlete at Boston College before returning to the Jesuit high school for boys to teach history. He later became a guidance counselor and helped countless students attend college.

Cotter is survived by his wife of 26 years, Agnes; two daughters and a son; and six grandchildren.

BC High spokesman Richard Subrizio said arrangements for Cotter’s wake and funeral Mass had not yet been completed Tuesday morning.

Lane Lambert may be reached at llambert@ledger.com.

The following story was published in The Patriot Ledger in 2006:

By MATT LYNCH

Only 17 years old, Jim Cotter sat in an exam room and listened to a doctor explain why the BC High football captain would never play the sport again.

Cotter spent six weeks in bed and six more in a hospital as his joints swelled to more than three times their normal size in the summer of 1954, before his senior year. The doctor told Cotter, the son of a Dorchester longshoreman, that he could never play contact sports again.

“I left his office and went to the car where my dad was waiting,” said Cotter. “My dad asked me what he said and I told him I was fine.”

Fifty-two years removed from playing careers at BC High and Boston College, Cotter is a Massachusetts high school legend, with a 236-149-17 coaching record from a 41-year career at BC High that ended in 2004.

He’s also a 69-year-old man trying to come to terms with ALS, commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Cotter was diagnosed in late October with the fatal disease that slowly kills a person’s nerve endings.

“I walked out of the doctor’s office, they had told me I had an appointment in three weeks, and I thought, ‘Where do I go from here?’” said Cotter. “I didn’t know anything about ALS. I’ve spent the last few weeks trying to learn more.”

What Cotter does know is that the last three weeks have resulted in a barrage of phone calls, letters and e-mails from the thousands of BC High students he coached and guided through his four decades at the school.

“Jim Cotter is one of the toughest guys I’ve ever met in my life,” said Leo Smith, a Pembroke resident and member of a 1977 Eagles team that won the Eastern Mass. Division 2 Super Bowl.

Almost everyone who attended BC High recognizes that description of Cotter, the intimidating coach, a living legend in a headset. But those who know the man spend more time talking about Jim Cotter the guidance counselor, who would do anything for any student, football player or not.

“He got a ton of kids into schools they had no business getting into,” said Jack Shields, a quarterback on the 1977 team and president of Quincy-based Shields MRI. “He always had a cause to help someone else. Never himself.”

Two years after Cotter retired, BC High President Bill Kemeza still lists the former coach as one of the school’s most influential members.

“I still call sometimes and ask if he knows someone at a particular school,” said Kemeza. “And almost always there’s no more than two degrees of separation.”

Shields vividly remembers the time Cotter put down a phone and picked up a snow shovel for kicker Brian Waldron.

After Waldron went unrecruited out of high school, Cotter set up a tryout with the Boston College coaching staff. But after six inches of snow on the day of the audition, the BC coaches told Cotter the session was canceled.

“Jim said, ‘No, it’s not,’ and went out and shoveled snow off the field so the kid could kick,” said Shields.

Smith said that kind of dedication is something Cotter brings to everything he does.

“He had that passion when I played 25 years ago and it’s still there today,” Smith said. “He would go to the ends of the earth for his kids, whether they were first on the roster or 53rd, or if he didn’t even play football.”

Cotter’s passion and toughness stem from his childhood in Savin Hill, where he and his friends would play tackle football down by the water and Cotter fell in love with the game.

“I’m very comfortable with my life,” said Cotter. “I’ve had a good life. I’m not going to feel sorry for myself. I never have and I never will.”

Cotter has made a career of defying doctors’ orders.

After recovering from the mysterious swelling – which was never formally diagnosed – Cotter earned a scholarship to Boston College, where he was diagnosed with a heart murmur.

Sitting outside the doctor’s office, Cotter watched as three other players entered the office with the same condition and left with their scholarship intact but their roster spot gone.

“I told (the physician) I came here to play football, and if you tell me I can’t play, I’ll leave school and go work with my father on the water,” said Cotter. “He said the only way I could play if I sign a waiver. I said ‘Where’s the paper?’”

Charlie Stevenson, head coach at Xaverian Brothers High School in Westwood, said Cotter’s teams reflected the sheer force of their coach’s will.

“His teams were always very tough and very well prepared,” said Stevenson, who has both coached and played against Cotter-led BC High teams. “They were always fired up emotionally to play us.”

Mark Stonkus, a quarterback on the 1991 BC High team, learned a lot more about Cotter’s intensity when he returned to the school as an assistant coach in 1997.

“Coaching with him is different than playing for him. As the quarterback, you get direction, you get the play and you go make something happen on the field,” said Stonkus, a Hingham resident and guidance counselor at the school. “As a coach, you’re standing right next to him with nowhere to hide.”

Former players said that once a student graduates from the school, his relationship with Cotter reaches a more familial level.

“When I was deciding whether or not I wanted to go to law school, out of my parents, friends and family, I called Coach Cotter,” said Brendan Bowes, a Quincy resident and 2000 graduate of BC High. “We went out to dinner, talked about it, and I decided to go to law school.”

Bowes was part of the last graduating class to play for Cotter, who retired when he realized his legs were too weak to last another season on the sidelines.

Current head coach Ron St. George said one of the true signs of Cotter’s classiness was that Cotter, for whom the team’ s new field is named, stepped aside gracefully for the new staff.

“It’s humbling to step into a program with the quality of a man like Jim Cotter,” said St. George. “Jim is a man of his word. He did exactly what he said he’d do.”

That kind of move isn’t surprising for a man so defined, Kemeza says he can read the text of an e-mail, with no signature and without looking at the return address, and instantly know if Cotter wrote it.

“You can even tell when Jim writes to you because he uses a big, Helvetica bold font,” said Kemeza. “You always know if it’s from him.”

Smith said that, at its root, the relationship between the coach and all of his former players and students is easy to grasp.

“We’re loyal to Coach Cotter and he’s loyal to us,” Smith said. “Not just in football, but in life.”