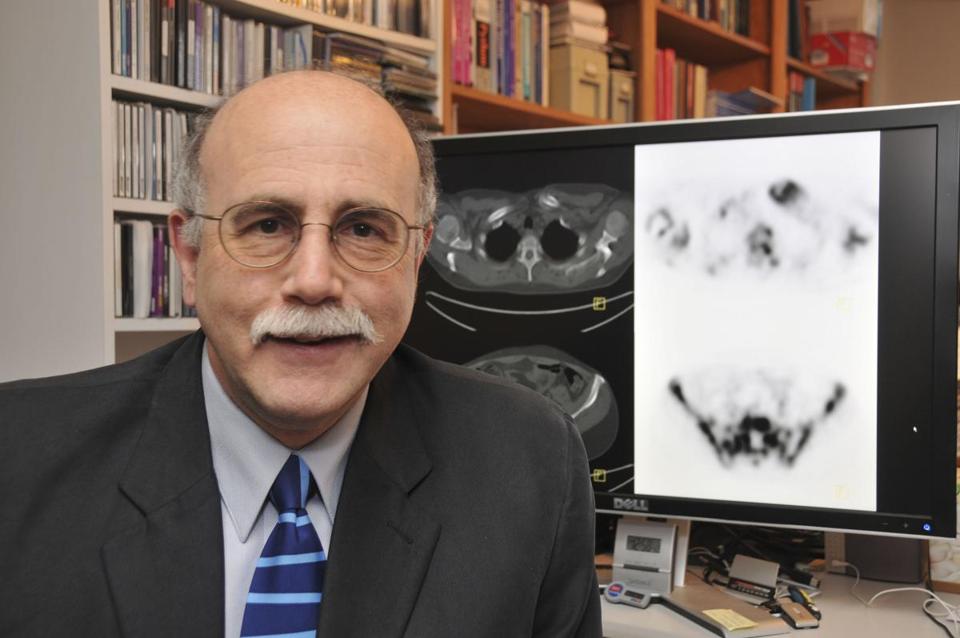

Dr. David Israel, 60; radiologist had knack for fixing what’s broken

Dr. David Israel, 60; radiologist had knack for fixing what’s broken

By Bryan Marquard | Published in the Boston Globe | February 03, 2014

“Repairing broken items wasn’t just a hobby — it was a philosophy,” Dr. Israel’s son said.

At the naming ceremony for his son in 1985, David Israel spoke of his own grandfather in Canada, a repairman who could make anything broken whole again. “I even thought he could fix a rainy day,” he told those who gathered that day.

The same could be said about Dr. Israel. As a radiologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, he helped other physicians mend bodies, and he just as skillfully restored shattered gadgets others might discard.

“For Dad, repairing broken items wasn’t just a hobby — it was a philosophy,” his son, Sol of Toronto, wrote in a eulogy for Dr. Israel’s memorial service last week.

“It was about mastery over technology and the joy of overcoming adversity,” he added, “of proving to yourself that any problem could be solved with belief in your own ability to learn something new.”

Dr. Israel, a physician whose true joy lay in the tinkering that is the lab researcher’s stock in trade, died in his Newton home Jan. 23 of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was 60.

“Honestly, the only thing he couldn’t fix in the 45 years I knew him was himself,” said his wife, Linda Matchan, a feature writer at the Globe. “With ALS, you don’t have any hope.”

And yet, until being diagnosed in 2010, Dr. Israel dispensed hope to others though an ability to repair seemingly everything he encountered on his journey from a basement workshop in Winnipeg, Manitoba, where as a boy he honed repairman’s skills, to his basement office at Dana-Farber, where as a radiologist he read scans of seriously ill patients.

“For me, patience is the virtue I will always associate with my Dad,” Sol said in an interview. “He was willing to wait for as long as he felt necessary to get good results.”

Dr. Israel did so with a calm resolve that many aspire to and few achieve.

“Most of us see anger as an automatic reaction that we have to have sometimes. I’m not sure he felt that way,” said his daughter, Sara of Boston. “I think he saw life as something you could approach rationally.”

At a key juncture, for the sake of family, Dr. Israel made the rational, if difficult decision to set aside his passion for research. Instead, he fell back on his medical degree, which afforded a more stable income than research, which depends on grants. Medicine may have been a second choice for Dr. Israel, who was 42 when he began his residency at Boston University Medical Center, but he brought considerable gifts and skills to radiology and nuclear medicine.

He had a “selfless commitment to help each of us understand the natural history of our patient’s illness,” Dr. Lee M. Nadler, senior vice president for experimental medicine at Dana-Farber, wrote in a eulogy. “Innumerable times I would leave the darkness of David’s reading room realizing that he had shown me a light that would help me make the next critical decision. David taught me the concept of a team of caregivers and he did it with his brilliance, wit, and humility.”

As a radiologist, Dr. Israel “was a master of putting all the pieces together to come up with the right information that’s needed for cancer patients,” said Dr. Nikhil Ramaiya, clinical director of Dana-Farber’s department of imaging. “Sometimes the answers are pretty straightforward, black and white. But most of the time, the answers are in the gray zone. He had this amazing knack of putting things together.”

The oldest of five children, David Alan Israel grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Winnipeg. His father was a lawyer, but he drew his principles and many of his talents from his grandfathers, one a watchmaker, the other a repairman.

“He valued everything old,” Matchan said. “He valued old connections of every sort.”

His basement bedroom and workshop housed treasures others didn’t recognize.

“Unlike a pack rat, who might save just for the sake of it, David could find a use for parts from a toaster made in 1969,” his sister Cyd of Toronto wrote in a eulogy. “I’m quite sure that some of the fancy machines he worked with at Dana-Farber were tweaked by him using only dental floss and a bobby pin.”

As a teenager, Dr. Israel changed high schools and in 10th grade met Matchan, whom he married in 1978.

“There he was, Prince Charming,” she said. “I literally knew from the first second I saw him that I was going to marry him.”

Expected by his father to become a doctor, he went to the University of Manitoba for his undergraduate and medical degrees, and then pursued biomedical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where “he found his calling,” Matchan said.

Dr. Israel received a master’s and a doctorate from MIT, where he was a research scientist. For several years when his children were young, he also was a research fellow and assistant biomedical engineer at Massachusetts General Hospital, and an instructor at Harvard Medical School. In his late 40s when he finished his residency, he became a staff radiologist at Dana-Farber.

In 2010, when he was diagnosed with ALS, Dr. Israel received a grant to research ways to refine the diagnostic accuracy of positron emission tomography, or PET imaging, in liver cancer diagnoses.

“He was so thrilled,” Matchan said. “He was happier than anybody could have been.”

But illness intervened as a promotion to assistant professor arrived and the grant offered him the chance to meld radiology and research.

“Even though this was a fate no one could have imagined, this may have been David’s finest hour,” his friend Dr. Leonard Leven of Elmsford, N.Y., wrote in a eulogy, adding that “his ability to smile and laugh when everything else he could do was gone, taught us not only how to die, but also how to live.”

A service has been held for Dr. Israel, who in addition to his wife, son, daughter, and sister leaves his mother, Debbie (Steiman) of Winnipeg; two other sisters, Susan Kliffer of Winnipeg and Judi of Vancouver; and a brother, Gary of Winnipeg.

“He had an appreciation for how things fit together and how beautiful the world was,” Sara Israel said of her father.

Dr. Israel found some of that beauty and precision in humor, where his tastes ran toward the music of Tom Lehrer and the comedy of Eddie Izzard. He could recite Monty Python’s famous dead parrot skit.

“If he were with us today, he would want us to laugh at life, to be silly and take joy in the absurd,” his son said, concluding his eulogy. “He would show us that any problem can be fixed and any tragedy can be overcome. All it takes is a lot of patience, the right tools, and belief in ourselves and the people we love.”

Bryan Marquard can be reached at bryan.marquard@globe.com.